Social movements are major drivers of cultural change and social progress (

1,

2). There is considerable interest in how social movements can most effectively resonate with audiences to shift public opinion (

3–5). Recent studies of “extreme” or radical tactics show that movements whose activists threaten violence or property destruction are generally less successful at winning public support than movements that do not (

6–10). Yet, social movements are not homogeneous in the agendas they pursue nor in the tactics they employ (

11,

12). Instead, they are typically composed of an array of factions with varying agendas and employing diverse tactics. A critical question is how this diversity within movements impacts the success of any given activist group.

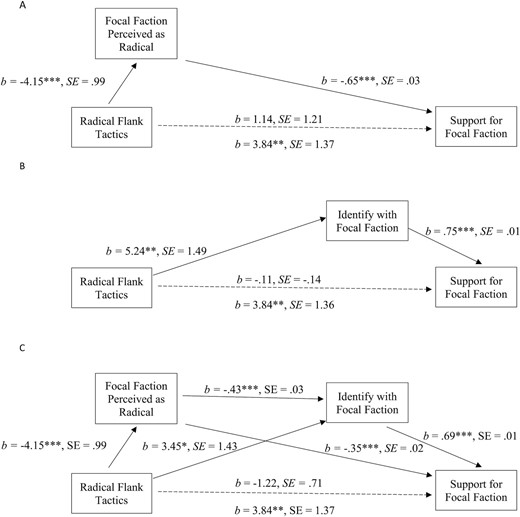

The literature on “radical flanks” addresses this question by asking how more radical factions impact the success of more moderate factions within the same movement, offering competing predictions about the direction of this impact (

11–14). The

positive radical flank effect hypothesis predicts that the presence of a radical flank—a discrete activist group within a larger movement that adopts an agenda and/or uses tactics that are perceptibly more radical than other groups within the movement—will increase support for a more moderate movement faction. The

negative radical flank effect hypothesis predicts radical flanks will decrease support for more moderate factions within the same movement.

Although there is little empirical support for negative radical flank effects, a number of correlational studies support the positive radical flank effect hypothesis (

11,

13). But other empirical tests find no evidence that radical flanks increase or decrease support for moderate factions within the movement (

14). Thus, the radical flanks literature has yielded inconsistent findings.